“I used to hate wild elephants because they pushed my family into debt. These animals also made it impossible for me to stay home. I had to stay put at my farm to prevent them from eating all my pineapples,” said Tui – Chanjira Phukang, a resident at Ruam Thai Village in Prachuap Khiri Khan’s Kui Buri district.

Prachuap Khiri Khan ranks among Thailand’s biggest pineapple baskets. Home to more than 402,000 rai of pineapple plantations, this province is a pineapple-processing hub with products sold to not just domestic but also overseas markets. Prachuap Khiri Khan is dubbed the “Capital of Pineapples” because it is the world’s biggest pineapple production base, which generates over 20,000 million baht of economic output yearly. Batavia is the most popular pineapple variety. It has nurtured the lives of so many Prachuap Khiri Khan residents in recent decades.

Speaking of Troubles

Thai farmers have faced various problems and challenges, which include climate change, rising production costs, falling crop prices, crop oversupply and pests. At the Ruam Thai Village that borders the Kui Buri National Park, pests are really big in size. They weigh a few tons each. Unlike other types of pests, “wild elephants” eat all crops fast. If they are not kept away, the whole farmland can be all ravaged.

Human-Elephant Conflicts (HECs) have posed big problems in many countries around the world. But they are mostly serious in Asia and Africa. Growing human population, the transition from agricultural society into agro-industrial society, fights for land, and the shrinking number of natural predators in the wild have worsened the conflicts throughout the past 20 years.

Thailand has witnessed the eruption of serious conflicts between wild elephants and people too. The problem has lately been reported in several locations such as the Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in Chachoengsao, the Khao Sip Ha Chan National Park in Chanthaburi, the Chaloemrattanakosin National Park in Kanchanaburi, and the Namtok Khlong Kaeo National Park in Trat. Nearly 400,000 farmers from 156,000 families have complained about damage to their properties and crops.

The Kui Buri National Park in Prachuap Khiri Khan used to be a fierce battleground for people fighting off wild elephants. Between 1995 and 1999, dozens of wild elephants were attacked. At least four were poisoned to death. Such tragedies made headlines and generated heated debates across Thailand.

Tui said her maternal grandparents settled down in Kui Buri and since her childhood, her family had grown pineapple trees for a living. As far as she remembered, she had lived mainly at her pineapple plantations because they were adjacent to a forest. If wild elephants wandered off their forest, her farmland was in the frontline. To protect her crops, Tui worked on the farm during the day and spent the night there too to watch over her harvest.

“I rarely returned home because I needed to stay vigilant. Sometimes, I also brought my kid to the farm out of concerns for her safety. If she stayed home, she would be alone,” Tui recounted about her difficult past, “It was stressful. My pineapple trees would give fruits just once a year. If all the pineapples were ravaged by wild elephants, I would lose everything. I took out a loan to get seedlings and fertilizer. If I could not harvest the yield, my hard work would be for nothing and I would also be deep in debt. That kind of pain was hard to heal”.

Humans or elephants, who are the real thieves?

Nitipat Naenkwan, head of the Ruam Thai Village, said his village was officially established on 1 October 1978 in response to a policy of the Kriangsak Chomanan-led government. Under this policy, degraded parts of forests were allocated to the poor. Each qualified recipient got three rai for their residence in a community zone and 20 more rai as farmland. The plots for allocations have been rented out by the Royal Forest Department to the relevant provincial administration. The farm zone sits north of the village and is directly adjacent to the Kui Buri National Park. Aside from addressing people’s bread-and-butter problems, this policy was also political in nature. The government expected the policy’s beneficiaries to help watch out against the Communist Party of Thailand at the height of communism threat.

In 1978, about 600 people from 150 families were beneficiaries coming to settle down at the Ruam Thai Village. Today, the village’s total population has grown to around 3,100 people or 770 families. Between 1977 and 1982, residents started pineapple plantations. From 1982 to 1994, pineapple plantations had expanded significantly in response to growing demand and soaring prices. The expansion brought plantations closer to the forest reserve. As wild elephants seasonally moved from high mountains to lower grounds, they thus could smell the tempting fragrance of pineapples. It was believed that wild elephants in the area tasted pineapples for the “first time” during this period.

From 1995 to 2002, fighting in Myanmar had intensified and wild elephants had learned from changing situations. The behaviors of the giant animals finally changed. They roamed longer around the borders of the forest and stepped out more to enter pineapple plantations. Farmers’ crops, as a result, were seriously ravaged. As damage piled up, violence peaked in 1999. That year, many elephants were killed. Academics described the confrontation as a “human elephant conflict”.

This conflict had reached the ears of King Rama IX, who then pushed for the “Royal-Initiated Kui Buri National Park Reserve Area Conservation and Rehabilitation Project”. This royal initiative has integrated efforts of relevant agencies through a tripartite committee namely 1) Security agencies via the 3rd Infantry Battalion, the 11th Infantry Regiment the King’s Guards; 2) Conservation and protection agencies via the Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation and the Royal Forest Department; and 3) Administration agencies. The provincial governor chairs a committee on occupational development. Thanks to the project, more than 20,000 rai of lowlands along the buffer zone were expropriated so as to give back natural spaces to the wildlife. People started stepping into the buffer zones in 1967 to clear forests for their eucalyptus, pine and pineapple trees. But the expropriation reversed the trend. Since then, the conflict has eased significantly.

Nature of Wild Elephants

Elephants are large mammals, with each grown-up elephant weighing between three and four tons. Two major species of elephants are African and Asian. Asian elephants are mostly found in India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand. An elephant fully matures at the age of 15. Its pregnancy lasts 22 months, after which a mother gets just one calf. The gap between pregnancies is usually at least four years.

In normal times, elephant population is well-balanced by the presence of natural predators, risks from baby deliveries, and attacks by male pachyderms outside their herds. Naturally, after elephants mature, their fatality rate is low. They usually will be able to live to the age of 60 to 70 years. According to the Department of National Parks, Plants, and Wildlife Conservation, there are between 4,000 and 4,400 wild elephants in Thailand. These pachyderms have roamed around 13 forest zones that span across 93 conserved areas. The birth rate among the population is around 8%.

Asian elephants can live in diverse geographical conditions from open fields to dense forests. Its food-search “radius” ranges from 180 to 400 square kilometers. Due to their big size, elephants spend between 14 and 19 hours a day on seeking food. Each day, they consume between 150 and 200 kilos of food. They also need to defecate 16 to 18 times a day. Their daily dung weight is around 100 kilos.

Wild elephants are dubbed “Key Contributors to Balanced Forests” because their eating, travel and defecation behaviors have maintained the balance of ecosystems. Their dung becomes natural fertilizer for soil and food for insects. As elephants roam a wide area and eat even crops on high trees, they spread around seeds. Small food scraps from their mouth fall to the ground and nourish tiny animals there.

Due to their biological conditions, elephants are sensitive to heat. So, they usually hide under tree shades or stay close to water sources in a bid to reduce their body temperature. They roam for food during the night and sleep during the day. Their hearing capability is superb. They can hear a sound even from a far distance.

Kui Buri Model

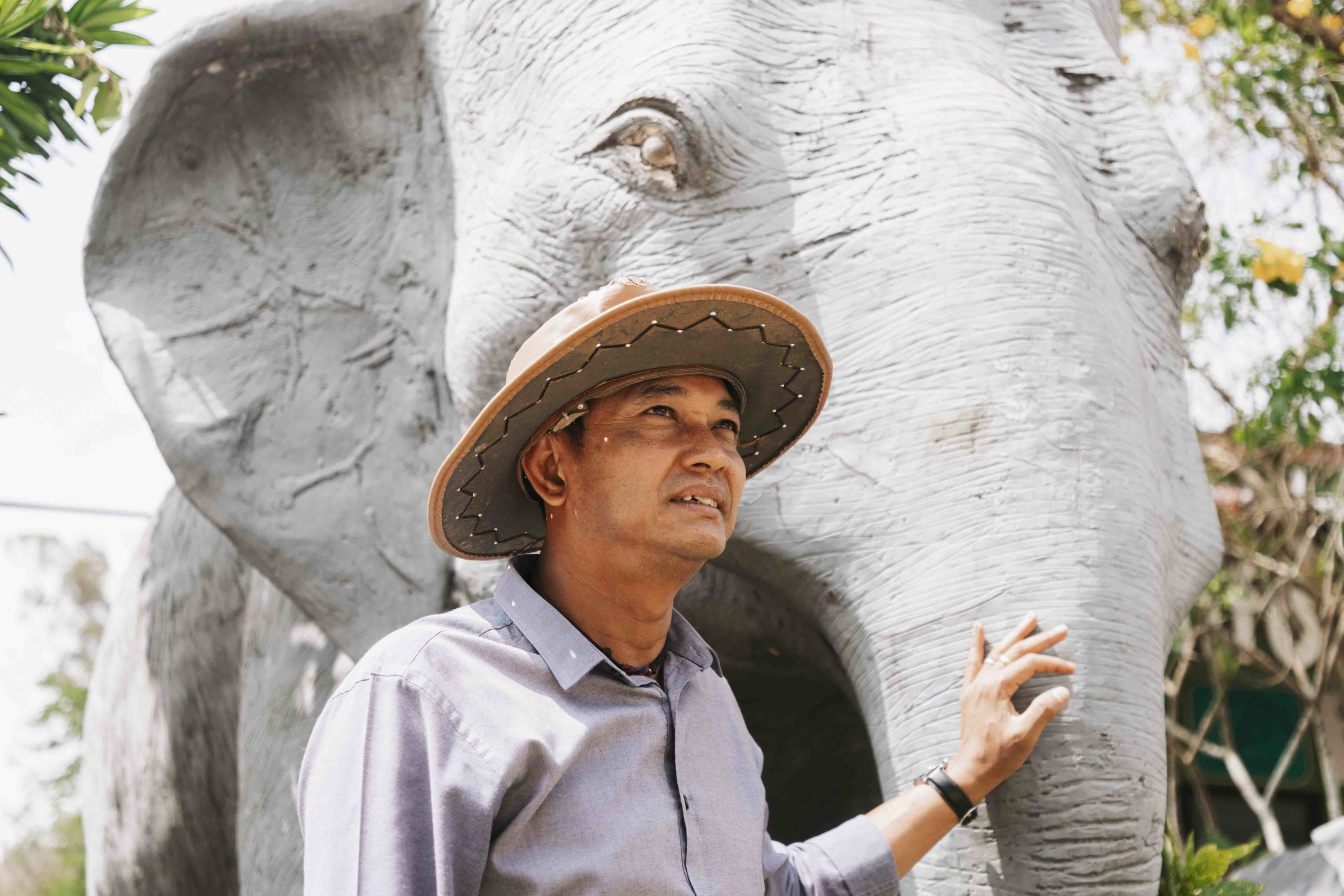

Attapong Pao-on, chief of the Kui Buri National Park, revealed that his park spanned over 1,000 square kilometers across four districts namely Kui Buri, Pran Buri, Sam Roi Yot, and Mueang District, Prachuap Khiri Khan. Boasting the abundance of wildlife and plants, the Kui Buri National Park is home to big herds of Gaur and Banteng. Its beautiful scenery includes the Tanaosri Mountain Range.

The wild elephant population in the area has increased to approximately 350 individuals as of 2021, up from 237 identified in the 2016 DNA-based survey. These elephants are observed in both large and small herds

Elephants that roam beyond the forest reserve have adversely affected local people, who reported more than 60,000 trees were ravaged. Worse still, wild elephants killed four people and injured two others too (data from 2007 and 2023).

“We must admit that wild elephants need forests to live in but the growing human population means we need more farmlands,” Attapong said. At its root, human elephant conflicts occurred because “both needed to eat”. As forest zones reduce in size, wild elephants have found fruit orchards are nearby and thus have eaten crops there. To introduce sustainable solutions in the face of many limitations, the Kui Buri National Park has prepared three approaches strictly in line with laws and regulations.

1. Prevention

The Kui Buri National Park focuses on ensuring the abundance of food and water resources in its zone so as to prevent elephants from straying off the border line. If wild elephants find they can survive inside natural forests, they will likely spend time in natural habitats. Wild animals need “salt licks” or a deposit of salts and essential minerals in order to obtain nutrients they cannot find in plants.

Climate change and humans’ growing farmlands, so far, have reduced the number of natural salt licks in the forest. The Kui Buri National Park therefore came up with the idea of creating “artificial salt licks” in support of wildlife management. Officials have designated spots where they mix sea salt with soil. When exposed to rain or dewdrops, salt melts and provides salt licks that various wild animals rely on. Recognizing that elephants need 200 liters of water per day each, the Kui Buri National Park has prepared water sources for the wild pachyderms too. Between 2008 and 2023, it has created 103 artificial salt licks, 18 earthen ponds, and 43 large cement water bowls.

2. Pushing Back

2. Pushing Back

Currently, wild elephants undeniably still wander off the forest zone into farmlands that used to be parts of forests and their sources of food. Pushing back elephants into current forest zone therefore is another approach to solving human elephant conflicts

The Kui Buri National Park has partnered with locals in setting up “wild elephant monitoring teams” to watch out for wild pachyderms that stray out of the forest reserve so as to prevent damage to people’s farms. In all, five teams have been set up for the central zone of the park. Each comprises between 10 and 15 members. The northern zone also has another team while the southern zone has one.

On top of these teams, the Kui Buri National Park in collaboration with people has established the “People’s Watch for Wild Elephants”. This network has attracted 11 members from 16 villages in six subdistricts of Prachuap Khiri Khan where the park is located.

- Engagement

As “empty stomach” is the root cause of the conflict, it is necessary to increase people’s income that is affected or threatened by elephant-related uncertainties. Another key jigsaw piece in efforts to solve human elephant conflicts is to engage people in the solutions via “tourism”. Utilizing existing resources, the engagement focuses on turning this crisis into an opportunity and changing local people’s hatred into love for elephants. Thanks to the successful engagement, “Kui Buri is dubbed Thailand’s Safari Paradise Now.”

“I believe Kui Buri Model is one of Thailand’s best models for easing human elephant conflicts. Thanks to the three aforementioned approaches, our solution has fostered good economy, happy society and sustainable environment,” the chief of the Kui Buri National Park said.

Although there is now light at the end of the tunnel where human elephant conflict in Kui Buri is concerned, implementation for sustainable solution does meet with several challenges.