In the past four decades, Thailand has been struggling with the challenge of area-based inequalities. Before the Covid-19 crisis, the Thai economy was worth 16.9 trillion baht, but 70 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) came from just 15 provinces, which are those of the Bangkok Metropolitan Area, Chon Buri, Rayong, Chachoengsao, Phuket, Songkhla, Surat Thani, Chiang Mai, Nakhon Ratchasima, and Khon Kaen, while the rest 62 provinces contributed only 30 percent to GDP.

Area-Based Inequalities

A deeper analysis of Thailand’s economic drivers reveals that the same 15 provinces have generated 88 per cent of tourism revenue, while the other 62 provinces, also known as second-tier provinces, have contributed just 12 percent of gross tourism revenue.

Asst. Prof. Dr. Nattapong Punnoi, a lecturer at the Department of Urban and Regional Planning of Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Architecture, said, “Area-based inequalities have prevailed in Thai tourism for a long time. Most tourists choose to visit only major provinces, which led to resource degradation and significant income equality.”

According to a report published by the Ministry of Tourism and Sports, the average length of stay for each domestic trip is 2.5 days, suggesting that Thais usually travel during weekends or long weekends. The joint research between dtac, Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Architecture, and Boonmeelab on mobility data for tourism promotion in second-tier provinces also came up with similar findings. According to the analysis, people mainly travel during long weekends with at least three consecutive holidays and are likely to visit a group of provinces, also known as tourism clusters, in a single trip. For example, those who travel to Chiang Mai might also visit the nearby Lamphun and Lampang or visit Phichit together with Kamphaeng Phet. The analysis shows that each cluster consists of at least one second-tier province.

“Our analysis reveals that tourists often visit second-tier provinces and nearby provinces in a single trip. With mobility data, we can see the potential to develop tourism clusters to increase the number of overnight trips and promote income distribution in second-tier provinces,” Asst. Prof. Dr. Nattapong explained.

Grouping Destinations Based on Travel Patterns

The National Tourism Development Plan 2021 – 2022 by the National Tourism Policy Committee highlights the importance of laying the foundations for the future and post-covid tourism recovery. The plan also suggests balanced tourism development in regard to area, time, activity, pattern, and types of tourists with the aim to generate income for the communities. Under the national plan is the “Action Plan on the Development of 15 Tourism Zones” that recognizes common selling points and shared identities of each tourism zone. For example, the Lanna Tourism Zone, which covers Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Lamphun, Lampang, and Phayao, shares the Lanna culture identity. The Andaman Tourism Zone covers the coastal provinces of Phuket, Phang Nga, Krabi, Trang, and Satun, while Nong Khai, Loei, Bueng Kan, Nakhon Phanom and Mukdahan form the Mekong tourism zone.

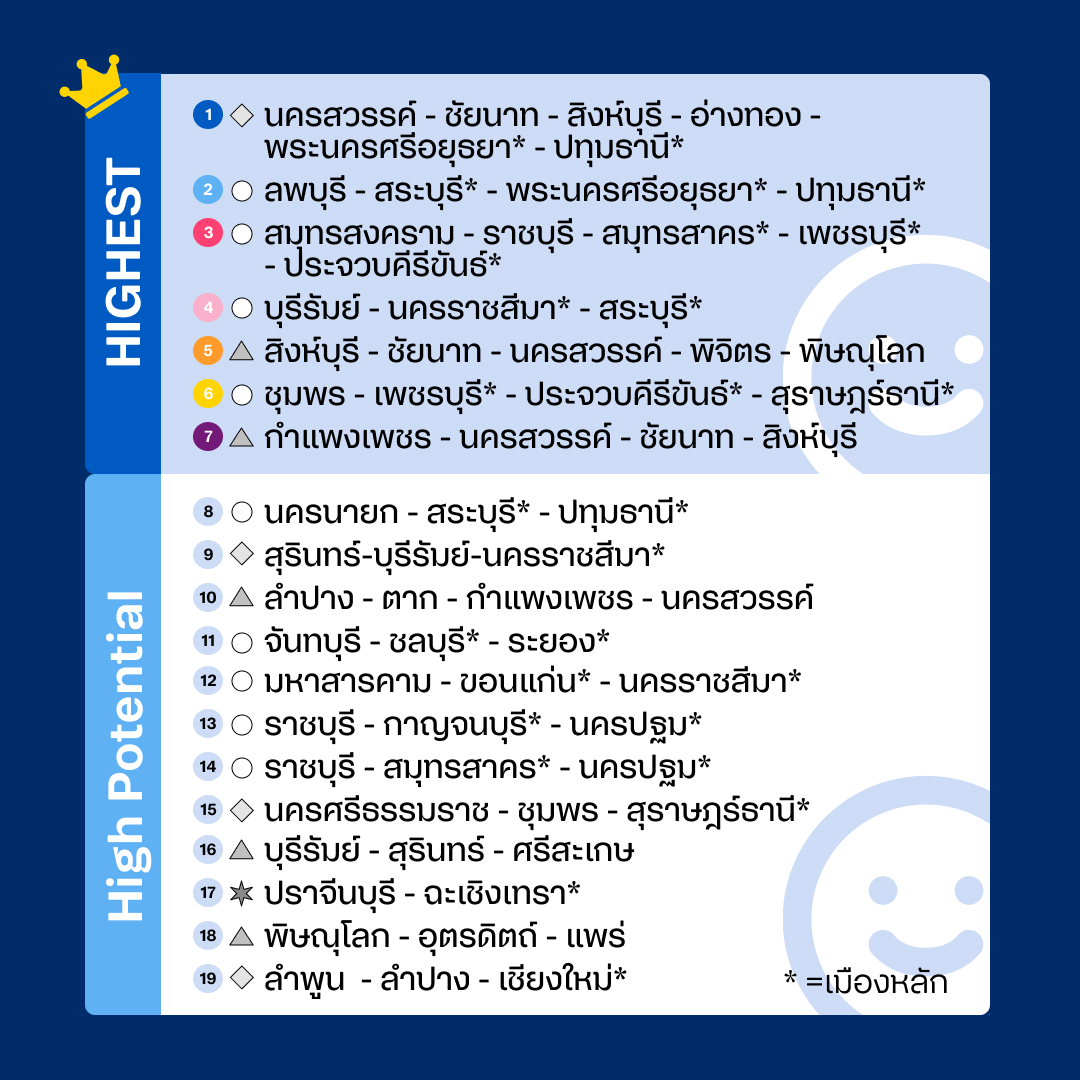

The development of tourism clusters can be improved with the use of mobility data. The team of researchers from Chulalongkorn University analyzed tourist travel patterns based on mobility data and was able to identify four categories consisting of 19 tourism clusters:

- Major Provinces-Dominant Category: This category features nine clusters. Each of them consists mainly of major provinces.

- Second-tier Provinces-Dominant Category: This category features four clusters. Each of them consists mainly of second-tier provinces.

- Second-tier Provinces Category: This category features five clusters. Each of them consists of second-tier provinces only.

- Twin Cities Category: This category consists of just one cluster, featuring two provinces.

The mobility-data analysis also reveals seven clusters with very high potential to develop tourism clusters due to a large number of interprovincial trips within the area:

- Nakhon Sawan, Angthong, Chai Nat, Sing Buri, Pathum Thani, and Ayutthaya (Secondary Provinces-Dominant Category)

- Lop Buri, Saraburi, Ayutthaya and Pathum Thani (Major Provinces-Dominant Category)

- Ratchaburi, Samut Songkhram, Samut Sakhon, Phetchaburi, and Prachuap Khiri Khan (Major Provinces-Dominant Category)

- Buri Ram, Nakhon Ratchasima, and Saraburi (Major Provinces-Dominant Category)

- Sing Buri, Chainat, Phichit, and Phitsanulok (Secondary Provinces Only Category)

- Chumphon, Surat Thani, Prachuap Khiri Khan, and Phetchaburi (Major Provinces-Dominant Category)

- Kamphaeng Phet, Nakhon Sawan, Chainat and Sing Buri (Secondary Provinces Only Category)

“

All these 19 clusters actually have potential for tourism-cluster development. Each attraction, activity, and interprovincial route can be connected through storytelling. The clusters can also jointly offer discounts for restaurants, hotels, and attractions within the area. Tokens may be introduced to promote tourism clusters too,” Asst. Prof. Dr. Nattapong stated.

The mobility data research findings were a surprise. For certain clusters, the distance between each province is relatively too far to be covered in a single trip and thus would not be considered part of the same tourism cluster; for example, the Phetchaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, Chumphon, and Surat Thani cluster. But social media suggests that travel within this cluster is popular for tourists from the central region and Bangkok, who will make their first stop at the old town in Phetchaburi for a temple and food tour and spend the first night at Hua Hin or Pran Buri district in Prachuap Khiri Khan. Then they will head to Chumphon to explore its food scene and spend a night or two in Surat Thani before heading back to their hometown.

Repainting Tourism Landscape

The mobility-data analysis also reveals travel patterns of tourists who visit a group of provinces in a single trip. This shed new light on tourism promotion strategy, which to date often regards Bangkok as a hub and air travel the major mode of transport. However, the latest analysis underlines opportunities to promote domestic tourism and attract tourists from nearby provinces. The analysis can also be used to design marketing strategies that better answer diversity in tourism and different types of tourists, such as road trip travelers and family travelers, who are growing in number in the post-pandemic era.

According to Asst. Prof. Dr. Nattapong, the past efforts to promote tourism in second-tier provinces, such as tax incentives and special discounts, were based on the “One Size Fits All” approach. This top-down approach helps stimulate demands but might not take into account differing characteristics of each second-tier province. This prevents each province from realizing its full potential. In this context, mobility data can help second-tier provinces to design a tourism development strategy that balances supply and demand.

“Countless untapped opportunities remain for Thai tourism. Mobility data enables us to better understand tourist behaviors and their travel patterns. It also helps second-tier provinces to realize their own potentials and shape tourism development strategy based on their true strengths and target audience,” he said. “This will enhance their capability to design suitable products and services for tourists, which is a key driver to increase economic value and promote equal income distribution.”